By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

June 17, 1999

As a child, director Mike Figgis was fat. One day in gym class, as a way to “encourage” him to lose weight, his teacher ordered Figgis to strip down to his boxer shorts and run through the gymnasium while his classmates swatted away at him.

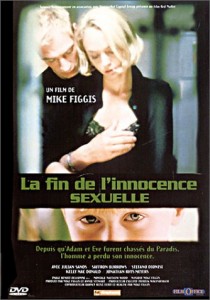

That cruel memory is poignantly re-created in Figgis’ latest film, “The Loss of Sexual Innocence,” which opens Friday at the Music Box Theatre.

“I was so ashamed of what happened that I didn’t even tell my parents,” said Figgis during a recent interview at the Four Seasons Hotel downtown. “I shot that part of the movie in a school where it had happened to me (in Newcastle, England). Before we started filming, the kids – who weren’t actors – actually started picking on the boy (George Moktar). They upset him so much that he started crying.

“At this point everything just sort of compounded. I was so upset when I found out that the boy was upset. I said, `OK, I’ve got a problem here. We’ve got to do a scene. In Hollywood, we have what’s called a stand-in or a stunt double for the star. My star is resting at the moment, so what I need is for someone to stand in for him. I need someone to run up and down, and I want all the other kids to hit him – not hard, but hard enough to look convincing.”

The startled students just stared at him. No one volunteered.

“I said, `Well, I’m lucky to have this film star George who really does have the balls and is brave enough to do this,’ ” Figgis continued. “He did the scene and afterward, all the kids applauded.

“But then this little boy put up his hand and said, `Excuse me, sir. But I think my father was at school with you.’ It was a complete coincidence, but his father was one of the kids in my class who had done that to me.”

Though there certainly are a few parallels to Figgis’ life, “The Loss of Sexual Innocence isn’t an autobiography. It was conceived as a mixed media piece, and Figgis wrote the first draft in 1982. He rewrote and tweaked it over the years when he had time. The relatively complex subject matter and nonlinear approach scared off some producers.

Then came Figgis’ highly touted “Leaving Las Vegas,” a project that gave him the clout to rally for his own cause.

“The Loss of Sexual Innocence” isn’t typical Hollywood fare. Highly ambitious, it asks filmgoers to think as they watch the movie. But like a good novel that rewards readers with a rich plot and a few twists along the way, this production treats viewers to one of the most unique pictures in recent cinema.

The movie centers around a documentary filmmaker named Nic, whose dispassionate wife longs for a different life. Figgis flashes forward and backward in Nic’s life so that the audience gets to know the character. We sense that Nic’s sexual innocence was lost when, as a five-year-old, he spotted a young girl clad only in lingerie reading to an old man.

As an overweight 12-year-old, Nic is emasculated at school by his classmates. At 16, Nic (played by Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, sporting Beatle bangs), has his heart broken when he catches his girlfriend making out with an older boy. And as a married man (played by Julian Sands), Nic engages in an affair that ends horrifically.

None of the actors who portray Nic bear a physical resemblance to each other. And it takes a few moments to realize that they do indeed grow up to be the same person.

“I didn’t do that intentionally,” Figgis said. “It’s a small film, so we were limited by time, budget and availability. So I chose the best actors. And I think it worked because at a certain point, the emotion is more important than the actual look.”

That emotion worked for co-star Saffron Burrows, who plays twins who were separated shortly after birth. One of them will work with Nic on an ill-fated documentary. Ironically, Figgis’ only complaint with her performance was that she was so convincing in her roles that some people didn’t believe that the identical twins she created looked alike.

Sitting in a separate suite at the Four Seasons, the tall, English beauty said, “Well that’s a very nice thing to hear. A couple of journalists have asked me, `Which (twin) were you?’ ”

Laughing, she added, “I loved doing the movie because it’s not something that comes along all the time. It’s not handed to you as, `Here is the story line.’ You have to find your own interpretation. What I enjoy about Mike’s work is that they’re very descriptive and evocative. So I knew that the dramatic interpretation would be pretty accurate in terms of what was on the page.”

The Nic story line is intercut with a parable about Adam and Eve (Femi Ogumbanjo and Hanne Klintoe) who, in an exquisite scene, emerge from a lake. They are completely nude, and yet the shots are less titillating than your average episode of “Baywatch.”

“I think when most people hear the word sex, they relate it to pornography because it’s such a pornographic culture,” Figgis said. “This entire industry is based on almost seeing a nipple. I’ve always observed in films that initially, you’re fascinated by nudity. You can’t help but check things out. Very nice. Whatever. Then you kind of get on with the story. Every so often your corrupted mind reminds you to check out the breasts or the genitals or whatever, just because it’s a condition. But after a while you just get used to it.

“I shot that scene as a wide shot. When someone’s coming out of a lake completely naked, but not in any way aware of their nakedness, there’s no coyness. Women are encouraged to behave in sexual manners. They’ve been conditioned to respond to a camera in a way that doesn’t create a natural look. My idea was you take away the clothes, and you put the scene in a wide shot where you’re in a natural environment and you find two actors who are prepared to do that kind of thing. So there’s nothing sensual or sexual about it.”

Asked whether he was afraid that an audience weaned on made-for-TV movies would get it, Figgis was adamant in his answer.

“I think the film is entirely accessible, in that there isn’t a single image in there that falls into the high-art category,” he said. “We’re living in a junkie culture where capitalism has oozed into every crack of the film industry that’s totally influenced by TV. There’s a paranoia that you might lose someone’s attention and, metaphorically, they might reach for the channel changer. So many film plots actually become secondary to the movie. . .

“The movie is designed as a crude pleasure, and as a filmmaker, you do become despondent about the level that you’ve been dragged down to. But even worse is the assumption that your core audience is also at that level, which I find very insulting. I refuse to believe it.”