By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

October 8, 2000

Jakob Dylan doesn’t believe in rushing the artistic process.

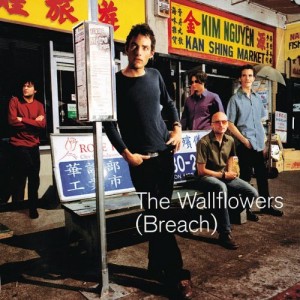

Four years after “Bringing Down the Horse” debuted, Dylan and his band, the Wallflowers, are releasing their third album.

“Breach” will be in stores Tuesday.

“We did [this new] record as quickly as we could,” says Dylan, phoning from Los Angeles last week. “The last record came out in 1996, but we were [on tour] until the middle of 1998. I was aware of a lot of time going by [between albums] and I wasn’t happy with that. I took some time off to rest when we got home from touring. But other than that, we got back to work right away.”

A lot is riding on “Breach.” When the band’s self-titled 1992 debut failed to make a dent on the album charts, the Wallflowers were dropped from their label. After switching record labels for their followup, “Bringing Down the Horse,” they sold more than 4 million copies of the album and produced a string of radio-friendly hits, including their evocative breakthrough single “6th Avenue Heartache” and “One Headlight,” which won two Grammy Awards.

As famous for his lineage as his reticence of talk about dear old dad (that’s Bob Dylan to you), Dylan has penned some surprisingly candid songs on “Breach.” In “Hand Me Down,” the handsome 31-year-old musician ponders his own worthiness with poignant lyrics that echo the uncertainty of having to live up to a legend’s reputation.

He sings, “You feel good and you look like you should/But you won’t ever make us proud.”

Baring such raw emotions, Dylan proves that at least the latter half of the lyric is incorrect.

Q. Do you feel that people are finally taking you at face value rather than as the Son of Bob?

A. There are always people who are going to be prejudiced and they like to dislike people like me. My family background makes it too easy for them to not like me. And they figure that my music can’t possibly be worth listening. That’s fine. Then don’t listen to it. But yes, for the most part I think that that has become somewhat irrelevant at this point.

Q. The fact is, Virgin Records didn’t care who your father was when they dropped the band after the first Wallflowers record came out.

A. I don’t really spend a lot of time discussing how hard [this business] can be because I think that everybody has a hard time no matter who you are. The unfortunate thing about coming from my background is that you don’t get the opportunity to just come out of the box and surprise people. People are predisposed to having an opinion before they even hear the music. But I suppose that’s also human nature.

Q. A lot of the early criticism about the Wallflowers basically boiled down to the fact that you’re not your father. When you read something like that, what does that do to you?

A. I can’t lie and say that it never hurts, because it does. There’s a certain time when there is a lot of criticism, but you make choices. Do you change the way you play because you want to be liked more? I suppose some people might, but we don’t. There have been times when I’ve read reviews that were not really positive and I didn’t disagree with a lot of what they were saying. I can see their point. But when you read things that don’t really have anything to do with the record or the show that you’re played, then that’s nonsense. It’s just people writing to make themselves feel better.

Q. What constructive criticism have you taken to heart?

A. [Laughs.] Well, there were some songs that critics pointed out as not being as strong as others. I spent a long time touring with the last record and I appreciated some of them a lot less by the time I got home. That’s why with this record, I wanted to write a record that was a lot more challenging. I wanted to be direct and a little more honest.

Q. But doing that meant revealing more about yourself and your background, and you’ve always been fairly reticent talking about either.

A. The timing felt right. I wanted to go in a stronger direction and I felt like the time was right to take a different approach. It’s true, though, that I can sometimes be quiet in interviews. It depends on what I’m being asked. On the last tour, I did a ton of press and sometime I would be asked just really dumb questions about growing up and what it was like. I think those things are just nonsense stuff and that’s not why I show up for an interview. It’s never my intention to offend anybody. But if 90 percent of your questions are going to be about my childhood, then I’m probably not going to talk that much. But if we have an interesting conversation about music, then, hey, I can talk and talk.

Q. Well, besides not talking about your family life, you’ve never really trashed any of your peers in a public forum. What’s that all about?

A. I find it unpleasant when people do that. I don’t use the press or television as an opportunity to say horrible things about people that I don’t know. To rail against those type of things isn’t going to get anyone anywhere. These [artists] who complain about it, I’ve always felt that if it’s that rough, then stop. Nobody’s making you do it. Get on the Internet and make your records and sell them yourself. But if you want to be in this arena and don’t like it, you can’t complain. Rock ‘n’ roll has been around long enough now that everyone knows what it’s about. It’s not uncharted territory.

Q. OK, but what if I brought up boy bands? Surely you could think of something to say about them.

A. [Laughs.] The climate is different now, but what can you do? You can’t let that influence you. You have to write the right songs for you, otherwise people won’t care what you’re doing. We finished touring [two years ago] right when that boy-band thing started. I’m not going to sit here and get harsh on any of those groups. They’re having a good time and making some people happy. The only reason it’s at all important to consider is that if something new doesn’t break through soon, then kids may not understand that there is something such as a Van Morrison and Miles Davis. They’ll never understand the harder material because when your mind gets numb with saccharine like that, it doesn’t have to work as hard to appreciate someone like Miles Davis. It just becomes too difficult.

Q. On this three-week club date, you’re pretty much playing 1,000-seat venues, which are much smaller than the theaters you played at the end of your last tour. How does that affect your psyche?

A. It’s what we need for now. I wanted to start out somewhere where the band was inspired to tour and where it was fun for us. We haven’t had a record out in four years. We played our first show in more than two years the other night in San Francisco. When we started out [on our last tour four years ago], we played clubs and filled them up. That’s when bands have the best times. You get to be with the audience right in front of you.

Q. Do you forsee a day when you’ll retire “6th Avenue Heartache” or “One Headlight” from your set lists?

A. I’m a firm believer that if people pay money to hear you play certain songs, that’s what you’re there to do. I’m not there to get my own rocks off. I can do that in the studio or at rehearsal. When fans pay money to see you play, you’ve got to respect that. Obviously, I want to play as much of this new record as possible, but I won’t do that at the expense of what the fans want.