By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

April 28, 2001

Margaret Cho has more than a few reasons to be bitter: At 8, Margaret Cho’s classmates dubbed her “Pee Girl.” At 12, she was ostracized by kids at church. At 14, she was raped by a 22-year-old man she met at a party. And at 16, Cho began a year-long relationship with a 26-year-old who tried to convince her to engage in a threesome.

Fast forward to 1994. ABC gave Cho her own highly hyped sitcom, “All-American Girl.” The first show built around an Asian-American actress, the series was supposed to make Cho a household name. Instead, it was canceled shortly after its debut and Cho was blamed for its demise by being too fat, not attractive enough, too ethnic, not Korean enough, a bad actress and not funny enough.

“I let them take away my voice with the show,” says Cho, phoning from her Los Angeles home. “I didn’t realize that without me, the show couldn’t go on. And by then, it was too late. I didn’t realize I had any power so I let them steer me in a direction that wasn’t what I wanted to do.”

After years of drug and alcohol abuse, hating herself for not being white and loathing the unfulfilled promise of stardom, Cho is clean, sober and at peace.

“In retrospect, I look at some of the things that really bothered me and think, ‘Why was I even worried about that?’” says Cho. “But when you’re experiencing it at the time, it’s the most tragic thing in the world that you hair won’t feather like the other girls. I went through a phase when I was maybe 12 or so where I wanted to be [actress] Lori Loughlin. I thought that if I was a skinny white girl with pretty brown hair and cute blond boyfriend, I would be popular and happy. There weren’t that many role models for Asian-American girls at the time.

“I also idolized Olivia Newton-John. I totally identified with her and wanted to be like her. She somehow didn’t really seem white, even though she was really white. She was foreign, also, so it seemed to me that she was more like me.”

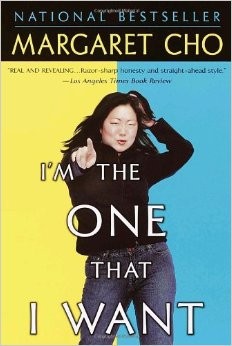

Cho’s career surged in 1999 when the comic, then 30, toured the country with her critically acclaimed one-woman show, “I’m the One That I Want.” A movie of the tour did well on the indie circuit. Her book of the same name debuts Tuesday and includes many of the stories she wasn’t able to squeeze into her play.

Candid, funny and often poignant, the book reveals a side of her childhood that even her biggest fans don’t know. Like many comics, she was an outcast in school. But Cho was ostracized to the point where she felt that it wouldn’t make a difference if she urinated during her grammar school music class. So she did.

At church with fellow Korean-Americans, Cho again the outsider. Short, a little chubby and a lot unsure of herself, she tried desperately to fit in with the kids who tormented her. The only place she felt truly comfortable was with the gay community that embraced her early on.

“Part of my problem is that I was a black sheep,” says Cho. “We have a difficult time in whatever community we come to. But the flip side is that we are the movers and the shakers of society. We’ve already been through rejection, so we end up making all of the real decisions in life and in other people’s lives. So the black sheep always gets to say, ‘Kiss my wooly ass.’”

Such as when former “friends” try to pretend they didn’t hurt her with their cruel remarks and behavior?

“Yes, something like that,” Cho says, laughing. “I wanted to tell the story of the pain as well as I could, but at the same time I didn’t want to write a vindictive book either.”

But come on, Margaret! Surely you must’ve felt at least a twinge of glee at being able to tell these people who had tormented you as a child to get lost!

“I’m not Mother Theresa,” she says, laughing. “There was definitely that pleasure in being able to embarrass these people who thought you would embrace them–especially at the time. But it doesn’t make me really happy to hurt people intentionally. I wanted to be as truthful with my story as I could, and part of that meant writing the bits that could be construed as embarrassing to them.

“I’ve changed some of the people’s names and characteristics somewhat so that they may not be recognizable to themselves. The emotions and the situations are real, but some of the people are composites. I did that when I could because I know that reading about themselves could cause pain, and I’m not trying to get revenge. I’m trying to tell what happened to me, how I was raised and how I came to see the world the way that I do.”

The book, which is dedicated to her parents, doesn’t always portray her mother and father in a positive light. But it also doesn’t vilify them or blame them for any of the problems she went through.

“Everything I do now is a reaction to growing up a certain way,” Cho says. “Everyone has their own experiences to think about. So in that sense, the book is incredibly raw and no holds barred. It’s a reaction to growing up with that secrecy of not airing your problems to anyone. Koreans believe that to share pain with others is selfish–that you should be good enough to keep pain to yourself and not spread your unhappiness around. I did that for a long time. And now I’m allowing myself be a little selfish.

“It was a long process but I’m very pleased and comfortable with my own skin finally. I like who I see in the mirror now. I don’t miss little Margaret. When I was writing the book and had to go back and edit, I was amazed that I had lived through so much. I couldn’t believe how much I survived and how much chaos, loneliness and insanity were such normal things to be for so long. It’s really interesting how much racial identity played a part of all that, too.”

Currently working on her next stand-up comedy show, which the rap fan has dubbed “The Notorious C-H-O,” Cho is a novice martial arts student.

“I sprained my ankle in tae kwon do class, so that’s my badge of courage these days,” Cho says. “I’m no good at it, but I’m having so much fun with it. I love being in a place where they speak my language and I understand it. It’s a great way to get back to my culture.”

And despite the alienation she felt as a child going to her Methodist church, Cho says she looks forward to the grace and pageantry of the non-denominational services she attends every week in Los Angeles.

“I’m not a practicing Methodist but I’m quite spiritual in my own way,’ she says. “I’ve always loved church, even though I have had a weird relationship with it. I just didn’t feel accepted by some of my peers when I was a kid. But I go to this really interesting church in L.a. now that has a lesbian minister. The music and the fashion there is fabulous, too. It’s a production! They have a beautiful gospel choir and we all look to see what everyone’s wearing I dress up to attend services, too, ‘cause I have to try to keep up.

“I think church can be a cathartic place because you remember that it’s good to forgive. There was a time when I blamed everything for my problems. I was an alcoholic because my show was canceled. My show was canceled because I was too fat. I was too fat because no one liked me. You can only pass things off for so long before you have to say, ‘Hey, I’ve got problems. What do I do to fix that?’ I feel like I have a good grasp of who I am, and I like who I’ve become. It’s just so interesting that this feeling of invisibility stays with you your whole life unless you go and do something about it. I’m not saying that I’m there yet. But I’m getting there.”

Excerpt from I’m The One That I Want (Ballantine, $22.95), by Margaret Cho

Lotte and Connie had a cousin, a shy, awkward girl named Ronny, who started going to our church. She had two older brothers who were really good-looking, with glossy, black feathered hair and tan, hard bodies, which made her popular by proxy. I was friendly to her at first, not knowing that she was to be my replacement.

One day Lotte came up to Ronny and me as we chit-chatted in the church parking lot. She looked at Ronny with a knowing glance and said, “Oh, I see you’ve met ‘MORON’!!!’ They both started laughing hysterically and I tried to be a good sport, accepting it as some healthy ribbing among friends, even though my face got hot and a knot grew in my throat.

Maybe I was paranoid. I hoped the situation would right itself [at] the church summer retreat. … I’d hoped to get a ride with Lotte and Connie, but they’d already gone with Ronny.

[At camp] all the kids had organized themselves into groups riding up together, and since I was late, and hated, I just stood there with my cowboy sleeping bag and tried not to look scared. … I hated myself and sat down on my cowboy sleeping bag. It made a crunching sound. I looked inside the bag. It was filled with dry leaves, pine cones, sticks and dirt–even dog —-! I heard laughter coming from outside the cabin. I recognized it. It was Lotte and Connie. I couldn’t take it anymore and I started to cry.

Not too long ago, Ronny came to a show of mine at the Punchline in San Francisco. She came backstage after the show with a group of her friends. She was thrilled to see me and wanted to talk about the days when we had known each other growing up.

“Hi–remember me?”

I took one look at her and said, ‘No, I don’t. I have no idea who you are.’ Then I walked away.