By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

June 9, 2001

Get over it isn’t exactly what you want to hear when your mother dies. Neither does hearing that your loved one looks good dead.

Yet the awkward words from the lips of our friends and family often add up to extreme insensitivity and hurt feelings, when it’s the last thing they mean. In the quiet moments after goodbyes have been said, it’s often hard to avoid dwelling on the hackneyed nature of sympathetic wishes. While we’d like to think of our well wishers in a positive, warm light, those of us who have grieved can’t help but wonder: “What were they thinking? Are they nuts?”

Lydia Davis Eady expected a little sympathy and respect when her mother–who also was her best friend–died. Imagine her shock when she was told to get over it.

“Less than a month after my mother passed, a woman told me that I was making too much of it,” says Davis Eady, a South Loop resident. This person said shed lost a brother and got over it, so it was high time I snapped out of it.

Something had to snap, and luckily it was not Eady; she quietly absorbed the comment and its sting, ignoring it.

“I was deeply hurt that anyone could say something like that to me,” says Eady, vice president of promotion for Johnson Publishing. “This happened 10 years ago, but I remember it like it was yesterday. It was really inconsiderate, but it also let me know who this person really was.”

Melissa Couty knows that death isn’t an easy thing for anyone to handle. But a person who has just lost a loved one shouldn’t be told how she should feel.

“My mother died of cancer five years ago,” says Couty, 31, of Fox Valley. “One guy said, ‘Oh, you know, when they’re sick like that, it’s just nothing but a relief when they finally go. There’s absolutely nothing to grieve about. It’s just such a load off your shoulders.'”

Another time, a woman blathered on about the cremation of Couty’s mother, who had requested this particular burial method.

“This woman went on and on about how cremation wouldn’t be her choice if she was dying. She just couldn’t see her kids doing that to her, or her doing that to her mother. Oh, she just couldn’t imagine! All I could do was look at her in disbelief.”

Unlike taxes, which were all trained to tackle each year, most Americans aren’t taught to prepare for death. We don’t know what to say. We don’t know what to do. Frankly, we don’t even want to think about it.

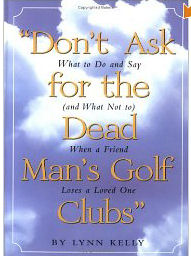

“Death is scary,” says Lynn Kelly, author of Don’t Ask for the Dead Mans Golf Clubs (Workman Publishing, $6.95). “It’s one of the last big taboos. We don’t know what to say because were afraid of saying the wrong thing. But if they don’t hear from you at all, it hurts them even more. I spoke with people aged 17 to 90 across country who had lost someone close to them. They all said the same thing–that the most important thing is to be there. Don’t worry about what to say. Say, I’m sorry, or I don’t know what to say. Just be there for them.”

That said, there are certain things that are better left unsaid. If you have the presence of mind to think before speaking, Kelly advises you to refrain from uttering the following:

—Don’t judge the way people grieve. Those who don’t cry can be just as devastated as those who can’t stop.

—Don’t make judgments. Some people might like to have a great big bunch of people over to sit there and tell stories. Other people might not want to do anything. You should be supportive about whatever makes your friend feel better.

—Don’t assume that because there are other children, the pain is any less.

—Don’t say, “I know how you feel.” There is no knowing how a newly bereaved person feels.

—Don’t jump in with a how or why, let them offer the hows. It doesn’t help to ask. When they’re ready to disclose details they will. What’s important is that the person is gone. Just say I’m here to be for you.

—Don’t make parallels with animals, as if the person could replace a lost spouse with a dog.

—Don’t say, “Don’t worry, you’ll get married again,” or “You’ll have another baby,” or “It’s God’s will.”

—Don’t make comparisons. Don’t say to a child who’s lost a parent, “That’s a terrible thing, but it’s worse for a parent to lose a child.”

—Don’t assume the death was for the best, even if the person was old, deformed or very ill.

—Don’t say, “You’ll get over it” or “Why aren’t you over it?” We want to remember the person we lost because we love them. If you still feel bad 10 years later that your child isn’t there to graduate with the rest of the kids, that’s OK. it’s Ok to feel bad and to cry.

—Don’t be nosy. If someone dies tragically or commits suicide, don’t say, “What’d he do that for?”

—Don’t be afraid to laugh. Laughter is healing.

—Don’t every ask for the dead man’s golf clubs. It sends a message that his loss is your gain.

“Being there, reaching out and holding the person’s hand—or giving them a hug or a pat—is far more effective than saying the wrong thing,” says Mary Ann Watson, a psychology professor at the Metropolitan State College of Denver psychologist. “You don’t have to say a lot, but you should think about what you’re saying. Telling them that the deceased looked peaceful or good is usually not well received. You’re basically saying that they look good dead. Is that the message that you really want to get across?”

If you’re not sure what to say, then do. Walk the dog, water the plants, fold the laundry. Make dinner, but make sure you label your dish or bring disposables so the bereaved won’t have to figure out what goes where later.

“It’s the simple things that are often the most appreciated,” says Watson.

That’s something that Eady keeps in mind. When it’s her turn to send her condolences to a friend who has lost a loved one, she passes along a poem she wrote after her mother died.

“A couple people have mentioned that they’ve put it on the wall to look at each day,” she says. “It seems to give them comfort.”

Compassion Fatigue and Satisfaction Indicators, Copyright, B Hudnall Stamm, Ph.D.

Helping others puts you in direct contact with other people’s lives. As you probably have experienced, your compassion for those you help has both positive and negative aspects. This self-test helps you estimate your compassion status: How much at risk you are of burnout and compassion fatigue and also the degree of satisfaction with your helping others. Consider each of the following characteristics about you and your current situation. Write in the number that honestly reflects how frequently you experienced these characteristics in the last week. Then follow the scoring directions at the end of the self-test.

1. I am happy.

2. I find myself avoiding certain activities or situations because they remind me of a frightening experience

3. I feel connected to others.

4. Working with those I help brings me a great deal of satisfaction.

5. I have happy thoughts about those I help and how I could help them.

6. I am pre-occupied with more than one person I help.

7. I have felt trapped by my work as a helper.

8. I like my work as a helper.

9. I have felt depressed as a result of my work as a helper.

Scoring Instructions:

Please note that research is ongoing on this scale and the following scores should be used as a guide, not confirmatory information. Be certain you respond to all items:

a) If you answered yes to items 4, 5 & 8, you have a good potential for compassion satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction is characterized by your pleasure in helping, likening of colleagues, good feelings about your about ability to help, make contribution, etc.

b) If you answered no to items 1 and 3, and yes to item 7, you may be at risk for burnout. Burnout is usually characterized by feelings of hopeless and unwilling to deal with work, onset gradual as a result of feeling one’s efforts make no difference or very high workload.

c) If you answered yes to items 2, 6, & 9, you may be at risk for compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is usually characterized by feelings of fear related to caregiving, it is often similar to post-traumatic stress disorder but is caring or work-related, usually with a rapid onset as a result of exposure to highly stressful caregiving.

For more information, check out www.isu.edu/~bhstamm.