By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

October 19, 2001

When Cleopatra is mentioned, beauty, sex and seduction are three words that almost immediately spring to mind.

But what about brains? More than 2,000 years after her death, the Queen of Egypt still reigns as one of history’s most famous and mysterious women.

There’s a new exhibit about her that hopes to clear up some points. A year after premiering in Rome, “Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth” opens Saturday at the Field Museum–the only North American venue for the expansive project.

For those expecting to see King Tut Part II, don’t hold your breath. While that exhibit glittered with jewels, gold, masks and, well, the mummified body of Tut, the Cleopatra exhibit deals more with ancient art that gives viewers a tangible account of who she was and, yes, what she looked like. Since her remains were never found, the exhibit is relying on anthropological conjecture.

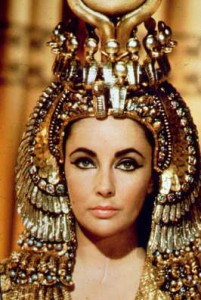

“Cleopatra was probably not much more than 5-feet-1,” says David Foster, the Field Museum’s project administrator. “She has been perceived through history to be a stunning beauty who subordinated Julius Caesar and Mark Antony with her looks, but the images of her on ancient coins that were minted during her reign show she was no beauty. Some of her closest ancestors were obese and some anthropologists have said she was probably short, dumpy and squat.”

By contrary, the classical portraits of her depict her as gorgeous and ethereal. Plutarch, who in A.D. 75 wrote the earliest portrait of Cleopatra in Life of Antony, said her physical beauty wasn’t of the kind that immediately commanded your attention, but her charisma, acute intelligence and powerful leadership did.

The exhibit, which encompasses 9,500 square feet of the museum’s space, includes sculptures, gems, mosaics, fresco fragments, coins, jewelry and metal work. Special tickets must be purchased for the the exhibit, and visitors will be limited to about 45 minutes.

“Many people may be surprised to see the spectrum of ancient art that is both Egyptian and classical,” Foster says. “She actually descended from the Greeks and was the last member of a 300-year-long dynasty that was put in place in Egypt by Alexander the Great.

“There is this monolithic idea of her as Queen of Egypt, but she and all her ancestors lived and reigned in Alexandria up on the coast of the Mediterranean. It was the largest, most populist and cosmopolitan city in the world at that time–kind of like the New York of its time. Multiculturalism is nothing new.”

After debuting in Rome, the exhibit moved to the British Museum, which had originally conceived the idea of the showing. (The production didn’t debut in England because the British Museum was under renovation at the time.)

Though basically the same in format, the exhibit has been adapted by each country to better reflect its own culture. In Rome, a room was dedicated to Cleopatra’s visit to Rome as Caesar’s mistress and her influence on the Romans. The London exhibit included a Victorian look at Cleopatra. And in Chicago–the show’s finale–a portion of the exhibit focuses on her relevance in pop culture.

“The core of the exhibit relies on ancient material and artifacts,” says Foster. “But the last section explores the legend. It allowed us to jump forward in time and follow the Hollywood spins of who she was. She is a phenomenon of Western culture. Since the Middle Ages on, she has been reinvented to fit what we wanted.”

The Field Museum has set up wall size projections to screen clips from some films about her, with actresses such as Claudette Colbert, Elizabeth Taylor and Vivian Leigh portraying her. Their costumes are also in display.

The Field Museum has been working on this project for the past 2-1/2 years. Design and production was handled internally. But when it came to fact checking, they sought out an Egyptologist to tie things together.

“We talked to the Oriental Institute about working with us,” says Foster. “We wanted to find an expert who would ride shotgun with us. We worked with Robert Ritner–a professor of Egyptology from the Institute–to put together this exhibit, which will hopefully broaden the public’s view of who this incredible woman was.”

By the exhibit’s close on March 3, 2002, the Museum expects the attendance record for the exhibit to exceed 200,000.