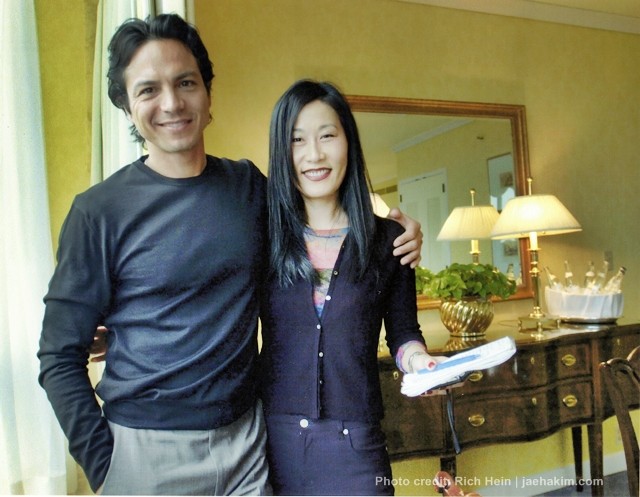

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

January 20, 2002

Fans accustomed to seeing Benjamin Bratt as by-the-book detective Reynaldo Curtis on “Law and Order” are in for a big surprise. In his first lead role since leaving the popular drama series, Bratt tackles the controversial life of Latino poet Miguel Pinero in “Pinero,” which opens Friday.

The 6-foot 2-inch, 185-pound actor grew out his hair, stopped shaving and lost almost 20 pounds to portray the Obie Award-winning playwright who developed a wicked heroin addiction. But the way the 38-year-old actor embodies the role with mannerisms that are as smooth and lyrical as the poems he recites is even more impressive.

On this visit to Chicago, though, Bratt definitely is more Curtis than Pinero.

Sitting in a suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Bratt–who is polite, funny and easy on the eyes–isn’t oblivious to the effect he has on the women fluttering nearby. Dressed in grey trousers, a tight black pullover and black ankle boots, Bratt looks every bit the movie star he is about to become. His almond-shaped eyes are liquid and chocolate brown, and the few strands of grey hair flecking his sideburns are his only concession to age.

With “Pinero,” he inhibits the mind, body and soul of a man who is unlikable for much of the film. Contrast that to recent co-starring roles in “Miss Congeniality” and “The Next Best Thing,” where he got to make cute with Sandra Bullock and Madonna, respectively.

“One of the things you wonder when you read a script about someone who lived is whether it’s going to be a flattering portrait,” says Bratt. “We were interested in telling a very accurate story of what this man was like. Miguel Pinero was not a hero in the traditional sense. He was a self-described philosopher of the criminal mind. That said, he was a kind of hero, especially to artists of color. His legacy lives on in the Nuyorican Poets Cafe art scene he helped found. He was an inspiration to those artists, and that is reason enough to tell this story.”

Pinero was 7 years old when his family emigrated from Puerto Rico to the United States. Shortly after settling into the Bronx, his father abandoned the family, leaving Miguel’s mother to raise the children herself. Pinero grew up on the streets of the Bronx, hustling, stealing and foraging for drugs.

In 1974, while serving hard time in Sing Sing, Pinero wrote “Short Eyes,” which won an Obie and the New York Critics Circle Award. He died of liver cirrhosis at the age of 41 in 1988.

“He burned bright and hot for a very brief amount of time,” says Bratt. “I can’t imagine him alive now being a counselor in a 12-step program. It’s not the way he saw himself.”

Pinero could be a sweet, charming man who’d give $5,000 of his own money to save a neighborhood store from bankruptcy. He would also help a friend rob another store, just because.

“My family saw the film for the first time [last week],” says Bratt. “One of the first things out of my mother’s mouth was, ‘There, but for the grace of God, go you.’ She was watching her son on screen in a completely different way, but thinking I could’ve ended up like that. She, too, was a single mother of five kids. She had a pretty amazing struggle to try to keep it all together, especially when we were on welfare. But it’s all about lifestyle choices.”

As with his love life–which routinely was dissected and analyzed when he dated and then broke up with Julia Roberts last year–Bratt doesn’t talk about his childhood, except to say he remains very close to his mother and siblings.

After graduating from the University of California at Santa Barbara, Bratt earned his MFA at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. He embarked on an acting career after graduation, but soon learned his exotic looks (his mother is Peruvian Indian, from Lima, and his father is German-English) hindered him when it came to winning roles.

“On some level, industry standards of how people of color are perceived and therefore hired reflect a microcosm of what exists in society,” Bratt says. “Unfortunately, that’s limiting. My early experience in Hollywood was disappointing and sometimes shocking. I remember winning a role in a movie-of-the-week and the character’s name was something like John Smith. It was a non-ethnic specific role and I had won it against many other actors from all walks of life. I showed up on the set to find out they had changed my name to Ramirez. I went up to the producer and asked why they did that, and he said it was a good opportunity to include an ethnic character. I pointed out to him that my last name is Bratt, and I’m reflective of millions of people just like me who are bicultural.”

Conversely, Bratt also is cognizant he may not have won the role of Pinero if the filmmakers had selected a Puerto Rican actor. Oscar winner Benicio del Toro and pop heartthrob Marc Anthony–both Puerto Ricans–lobbied for the part Bratt won. One wonders how Pinero himself would’ve reacted to the choice, given that he once lamented on the sorry state of Italian actors being selected to portray Puerto Rican characters.

“It’s definitely a sensitive issue and I have many different opinions about it,” Bratt says carefully. “As an actor, I should have the freedom to play any role that someone wants to offer me no matter what the background of the character is. That said, we know that Hollywood is set up so it’s less likely an actor of color would get a part over an actor of European descent. Then you have a case like ‘Pinero’ where it’s vitally necessary to have Latino elements in place–otherwise it just won’t work.”

But as far as the filmmakers were concerned, Bratt was the man for the role.

“Benjamin was fearless about going after the role,” says “Pinero” writer and director Leon Ichaso. “He’s the one who really wanted it. He was very charismatic in his auditions. He had that combination of devil and angel that was very seductive and very much a part of who Pinero was. It showed in his eyes, and that was the clincher for me.”

Of criticism the film has received that Bratt simply is much too handsome to portray the tortured poet, Ichaso doesn’t deny Bratt’s beauty.

“The problem with Ben is he looks better bad, don’t you think?” says Ichaso. “But Pinero wasn’t an ugly man either. He just wasn’t as good looking as Ben.

“I still remembering meeting Miguel for the first time in 1981. An actor friend and I were smoking a joint in New York’s Central Park. Miguel crawled out from under some bushes. He had fallen asleep on an ant hill and he was scratching himself. I thought he was homeless. We shared the joint with him and after he smoked it and it came back to me, I would wipe off the tip with my shirt. He looked that dirty. He had a little notebook and pencil and said he was working on a play. I don’t think I believed him until my friend told me who he was.”

Throughout the month-long shoot, Bratt walked around New York unshaved, hair unkempt and wearing polyester clothes that had seen better days, if not years. No one recognized him, which wasn’t all bad for the actor who had been hounded by paparazzi during his Julia years. But he couldn’t pay anyone to take him cross town.

“I don’t subscribe to that notion of being in character when you’re not working, but on a superficial level I took Miguel wherever I went because I had his look,” says Bratt. “For the first time in New York City, people who looked just like me would pass me up. Even cab drivers wanted nothing to do with me. It happened enough times to give me a taste of the other side.”

One time, he sat outside a hospital after shooting a scene, looking so morose and pathetic, that a woman gave him a quarter.

“That’s more money than I paid him,” jokes Ichaso. “We didn’t have a budget for big egos.”

Bratt and Ichaso are realistic about the potential success of “Pinero,” which was made for $1 million in 25 days. They realize the film will appeal to a fringe sector of the population who are intrigued by the notorious poet and another faction that wants to check out Bratt.

For the actor, the film is a star-making vehicle that showcases his lucid versatility.

“I never approach a role considering the ethics of a character,” says Bratt. “What draws me to a role is the complexity of the person and whether or not it’ll be interesting and ultimately challenging to play. That’s the biggest draw for me. I reckon there won’t be another role like Pinero for many years to come. It was the chance of a lifetime.”

While he doesn’t dismiss the possibility of guest starring on “Law and Order” or doing another television series (“Television has been very good to me and I’m grateful to it”), Bratt’s next role will be on the big screen. In April, he begins work portraying a real-life soldier in Mirimax’s “Great Raid.”

“They beauty of my job is I get to walk in so many different shoes,” says Bratt. “One day I’m a gang banger, the next day I’m a drug kingpin. Then I’m a poet and a playwright, and the next day I’m a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. Try to beat that.”