By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

February 13, 2004

It will be a bittersweet Valentine’s Day for Joseph Shabalala when his band Ladysmith Black Mambazo plays a sold-out show at the Fermilab National Accelerator Laboratory in west suburban Batavia.

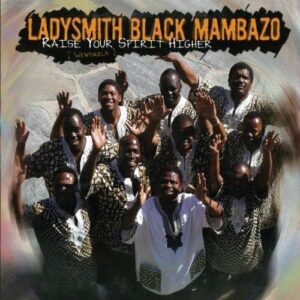

Touring to support the group’s recently released album “Raise Your Spirit Higher,” Ladysmith Black Mambazo will be performing many songs that Shabalala wrote for his wife, Nellie, who was murdered outside a church in South Africa two years ago.

“When I am sad, I remember that every day the creator makes something beautiful,” says Shabalala, 63. “I wish people — black and white — would have a vision not of fighting and killing, but a good vision that comes with love.”

On their current album “Raise Your Spirit Higher,” the 10-member group celebrates the 10th anniversary of the end of apartheid with songs that may surprise some fans. Yes, there are the introspective political songs that have helped define the group’s soaring music. There also are gorgeous gospel numbers (both Christian and Zulu) that show off Shabalala’s moving voice. But the band also delves into a little rap when it tackles the blues classic “I’m So Glad.”

The South African band won critical raves when it appeared on Paul Simon’s “Graceland.” The group, which formed in the 1960s, hadn’t anticipated the Western world would be so receptive to their music.

“We were very surprised when we began to get popular [in America],” says Shabalala. “We said, ‘What’s going on?’ But it was almost more surprising when white people in Africa would come up to us and whisper to us that they thought our songs were beautiful.

“I remember my brother, who has passed away, said, ‘Hey, people are talking about you,’ which could mean a good thing. But we didn’t hear that they were [necessarily] saying good things about us, so we weren’t sure how to take it.”

Shabalala lets out an infectiously catchy laugh. When he speaks, it is in a melodious cadence that is as rich and sweet as when he sings.

“Things are so different and wonderful from when we first started recording,” he says. “Back then, we were afraid we would lose our voice if we recorded a song. We had heard these records and the [musicians were all dead]. We thought that would happen to us, too. But we thought that we would be able to live on through our music, so we took the chance.”

Nevertheless, Shabalala says the singers would cough after each recording to make sure their voices remained intact.

“Back then, there was a lot of segregation and discrimination,” he says. “We thought white people were going to steal our voices. It was a very, very different time. But it was also a magical time.”