By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Substack

December 4, 2023

If you like K-pop and are on social media, you’ve probably seen the uproar regarding the latest NYT Popcast episode: Jung Kook, BTS and English Language K-pop: A conversation about K-pop’s long march into American awareness, and the potential risks of that embrace. The thesis of the 47-minute podcast is questioning whether K-pop is still K-pop if sung in English. It also questions whether Korean artists should even be singing in English, since there are so many Western artists who already sing in, you know, English…

Let me start out by addressing what K-pop is: it’s a short-hand term for Korean popular music, particularly idol music. Most Westerners, however, use it as a term to describe any Korean musician, whether they’re idols or not.

Listening to this podcast, the first thing that popped into my head was: this episode wouldn’t exist if a white musician — from a country where English was not the official language — released an album of English songs that debuted at No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Album Sales chart. I don’t recall any hullabaloo when artists like ABBA (Sweden), Scorpions (Germany), Celine Dion (French-speaking part of Canada), Bjork (Iceland), Kraftwerk (Germany) etc. sang almost exclusively in English.

Why was that? Was it because they looked like they could speak English, while BTS and their youngest member, Jung-kook, look like they can’t because … Asian? I often talk about how Asian diaspora suffer from perpetual foreigner syndrome — where even if we were born and raised in Western countries, many people assume we must be from somewhere in Asia.

In this podcast, there are some slip ups that are minor and unintentionally incorrect. The show’s host, Jon Caramanica, refers to Jung-kook at one point simply as Kook. It would be like calling me, Ha. Or to use a Western analogy, referring to someone named Philip as, Ip.

He goes on to introduce his only guest, Kara. He says he won’t reveal her last name because “the stans are crazy. And anybody who listens to Popcast knows about the ongoing struggles between people who try to think critically about pop music…and people who tweet.”

So let’s get into some aspects of the podcast:

15:37 minutes

Kara: The goal, I think, as a K-pop idol is to break out of the screen. You can’t dance in high heels forever. Jessica Jung from Girls’ Generation is very involved in fashion. Acting is a big one and “Parasite” just won the Oscar, so that whole acting world is another way to get the stars exposure, get them on the movie screen. Get them on your TV screen. So someone like Taec-yeon from 2PM, he was in a Netflix drama. These are other avenues that intersect with other forms of celebrity.

I’m not going to pick apart everything she said, because many K-pop idols are trained in acting, as well as singing and dancing. And Taec-yeon’s more of an actor now than a rapper and was very good in the drama she’s referring to: “Vincenzo.”

However, what does “Parasite” have to do with K-pop?!! There are no K-pop idols in the film. The only thing that the film and K-pop have in common is that Koreans are involved.

I understand that things may be said during a chat that aren’t correct. But why wasn’t this error edited out of the final production?

19:41 minutes

Kara: And then in 2017, 2018, [BTS] began morphing into more of a group aimed at an American boy band audience rather than a band aimed at the American K-pop audience. And I think the way they were received in America was as a boy band. I think of it as their One Direction era, because they’re using some of these same songwriters. It’s the Jonas Brothers. It’s that era.

20:22

Jon: Do you think “Mic Drop” is where they pivoted? Was it “Fake Love”?

Kara: For me I think it was “Mic Drop,” because they got on Steve Aoki. Just to my ears, I didn’t really understand why they had this big touted collab with a guy I’d never heard of before. I don’t follow EDM so…

Jon: It’s also not that big — no shots to Steve Aoki — it’s not that big of a get. Like out of all of the gets that they’ve gotten, it’s not that big of a get.

First of all, if you’re a music writer and you don’t know who the Grammy-nominated Steve Aoki is, that’s on you. Secondly, I honestly don’t get the impression that BTS is too concerned about clout chasing. They were already famous by this point. They’ve said that they wanted to work with Aoki because he’s a talented musician, and there’s a certain comfort in working with a fellow Asian. Aoki echoed that same sentiment in an interview I did with him. Personally, “Mic Drop” is one of my favorite BTS collabs. It suits my musical sensibilities.

30:25

Jon: Why not just make essentially neutral, generic English-language pop by the most famous band in the world and then boy, it’ll end up at the top of the charts, which is exactly what happened. That’s how it feels to me, but doesn’t that on some level damage what BTS has been good at up to that point?

Kara: I would think so. I was in a small group of fans who — we had liked BTS previous to a lot of this.

Jon: Safe space. Don’t tweet us. We’re grown ups.

Kara: We had drifted away, because this was not anything I wanted to listen to. It didn’t sound like the group that I had enjoyed. Even with BTS being that chameleon group, they were able to handle a bunch of different styles and do them well — but this was a step too far for me.

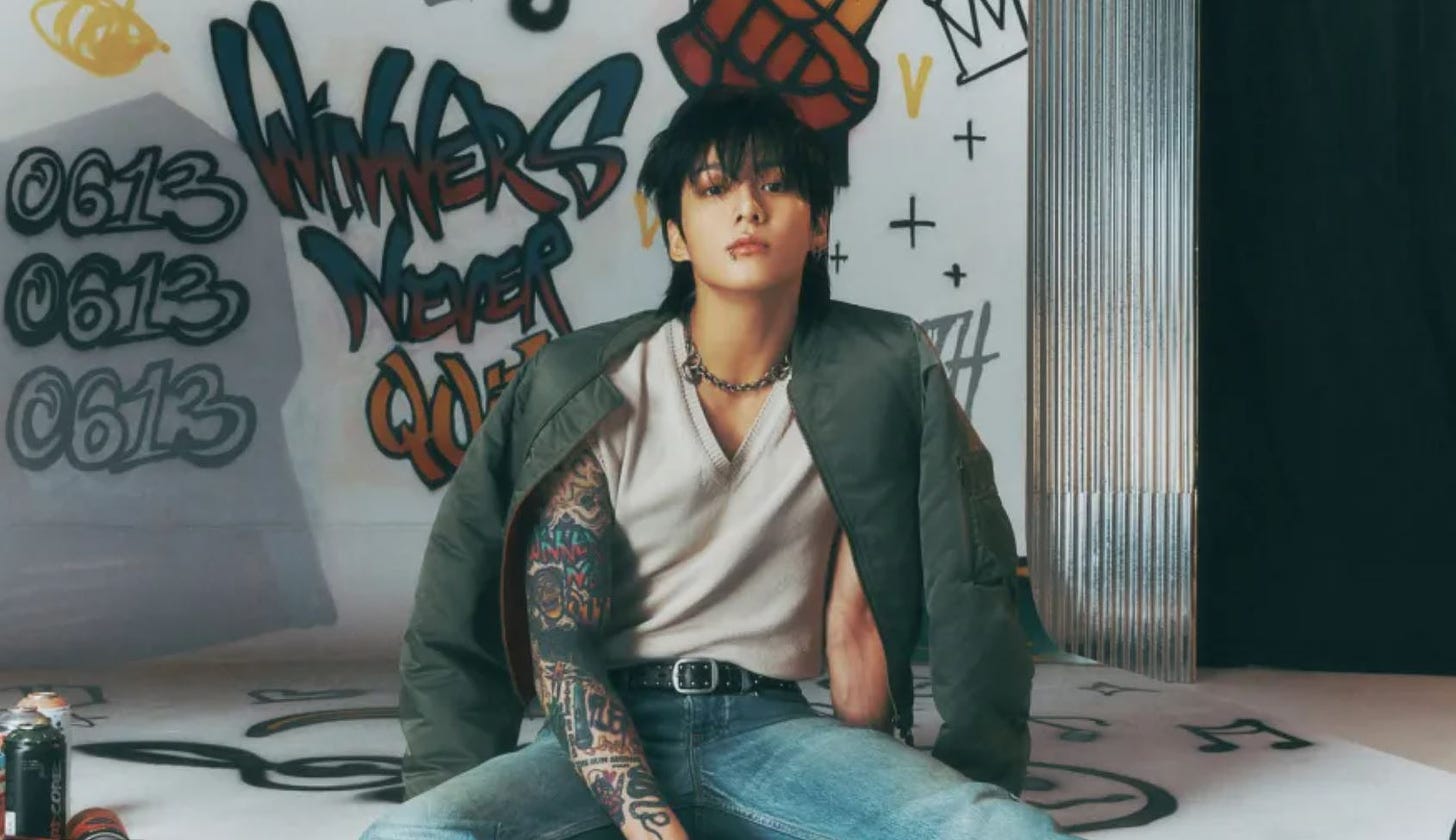

Jon: If you’re taking a devil’s advocate position, “Butter” proves a point, which is the biggest, most popular English language — in quote marks — music act, boy band, pop act, need not derive from America or from Europe. That group can come from anywhere. I think that’s a valuable contribution to how pop globalization is understood. That said, it seems like a genuine aesthetic [NOTE: I’m not sure if this is the word he said] set back for this group in particular. And then if we’re going to move into the solo projects… I think the Jung-kook album is really instructive. I kind of waffled on this album a bit when I first listened to it. … Here’s an album — I don’t think there’s any Korean. And what does that tell you, that for Jung-kook at this stage of his career, that is the direction that folks chose to go. And collaborations with Latto, Jack Harlow and this Justin Timberlake thing.

Kara: To me, it sounds like listening to Top 40 radio and getting a nice sample of everything on the charts right now. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a very serviceable mainstream pop album.

33:50

Jon: Is it wrong in this moment then to ask the broader question of: Is K-pop being stripped on some level of the singular thing that made it so fascinating? To me, I think, I would’ve been way more excited to hear whoever the next Justin Bieber is trying to make records that sound like K-pop records than hearing Jung-kook trying to make records that sound like washed up Justin Timberlake records.

Kara: That Justin Timberlake remix is something else.

Jon: Yes, that’s not it.

Well, actually… earlier this year, Korea’s JYP Entertainment and America’s Republic Records held the reality singing competition “A2K” to select members of its first American K-pop girl group: VCHA. They’ve already released their pre-debut single album, “SeVit (New Light).” The members hail from the U.S. and Canada. Its sole ethnically Korean member is the group’s maknae, Kaylee, who was born and raised in Washington state.

Blackswan (members hail from the U.S., Senegal, India and Brazil) is still around. The boy band EXP Edition included members from Croatia and the U.S. The only ethnically Asian in the group was half Japanese and German. And the London-based girl group KAACHI disbanded in 2023 after a scant three years in the business.

I think, though, that what Jon was getting at was that it would be more interesting for him as a K-pop fan and listener if a popular Western (non Asian) artist gave K-pop a shot.

But what does that even mean? The K in K-pop stands for Korean. There has to be a Korean element to K-pop. A foreign non-Korean member singing in Korean? Sure, why not? However, the very Korean Jung-kook singing in English doesn’t negate his innate Korean-ness. It just adds another layer to his work.

[I lost track of the time code, sorry!]

Jon: What’s being lost here?

Kara: It’s an attempt to make American music, but just by a Korean. There really is no K-pop in this album other than the audience listening to it is a K-pop audience. That’s what makes it K-pop.

But wait, earlier in this same podcast, she said that “[BTS] began morphing into more of a group aimed at an American boy band audience rather than a band aimed at the American K-pop audience.” So which is it? And isn’t it possible that there’s an intersection of fans who like both K-pop and boy bands of various nationalities?

What makes it a K-pop album is that the Korean artist wrote and recorded it.

Jon: If this same exact album had been made by a different artist, I think it just goes by. If it was by Jimmy Wilson or some random American guy.

Kara: It would go in one ear and out the other. The only thing that makes it notable is whose face is representing this. But I do agree that something is lost there because there is a sound to K-pop. But previously there was this real eclectic drive to pick up pieces from here and there and use new sounds, use new and bigger and brighter colors and costuming and just get the weirdest stuff that you can find and throw it on screen. And there are still acts doing that. I heard a song that other day. It sounded like a country-music style guitars all through it and it was great. It’s frustrating because now when people think K-pop, they do think of “Butter.”

One of the things lost in this conversation is that BTS debuted 10 years ago, when all but two of the members were still in their teens. To expect them to continue making music they’ve already done — without experimenting and growing — is to strip them of their artistry. You can like their earlier work. You can dislike their later work. You don’t even have to like them. But one thing you have to give them credit for is that they are willing to try new things — like including traditional Korean instruments in their pop songs — and working with musicians some of their fans don’t even like.

In several interviews that Jung-kook did to promote his solo album “Golden,” he said that he wanted to experiment and try new things. He listed a bunch of other genres he’d like to try in the future, including classical and musicals and perhaps even opera. Will he do all that? Maybe yes, maybe no. But the point is, thinking about what you’d like to do is part of the process and a way of growing as an artist and as a person.

38:23

Jon: But here again is the devil’s advocate for you. It’s inherently meaningful that the most pop American pop album of this year was made by someone from South Korea. From a K-pop boy band. That to me is where I’m pulled in both directions. Because on some level, I think that’s inherently valuable or interesting or thought provoking — and [it] would encourage non K-pop listeners to think hard about the pop music they consume and say, “Huh, that’s fascinating. I’m getting this very similar product that also sounds like the other things I like, but it’s coming down a different pathway.

Kara: It’s not though. That’s the thing. All the writers, all the producers, it’s an American album with a Korean face on it basically. So I think if I was a listener that was like, “Oh, this is what a K-pop guy can do? It sounds just like Justin Timberlake.” Why do you need a Korean guy doing Justin Timberlake when we have Justin Timberlake? I can go see “Trolls 3” right now. I don’t need to fly to Seoul to see “Trolls 3,” right? It’s here. [NOTE: the film title is actually “Trolls Band Together.”]

OK, so let’s address this. Why, then, do we need any white guy doing music like Justin Timberlake, or Ed Sheeran, or Troye Sivan or … you get the picture. They already exist, so why should other white creatives be allowed to sing similar types of songs? And let’s take this a step further. Chuck Berry and Little Richard were already singing songs that would be covered by white musicians like Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. Chuck and Richard already existed. So why do you need a white guy singing songs by Black musicians who sang it better anyhow?

Why? You know why. White people singing Black artists’ music was considered more palatable and marketable.

And I get this feeling that hearing English language songs by Korean artists makes a certain sector uncomfortable for a variety of reasons. It’s the same feeling I get when I hear white people say they lost opportunities because it went to minorities instead. As if the spot was owed to them.

And, obviously, not all white people. Just the a-holes.

Jon: Are we trying to protect something that in Korea amongst the core fan base, those fans are like, “This is fine. I have no problem with this.”

Kara: From what I understand, I don’t think we’re off base. Even going back, we were talking about Big Bang, but [their album] “Alive” came out, which was such a great album, but there were complaints even back then from fans that it was too global, it didn’t sound Korean enough. So there are always going to be those people that don’t like change, that don’t like a global sound. But I think in this case, I have heard a lot of complaints from fellow fans, fellow fans not in America, fellow fans in Asia, that this just isn’t what we’re looking for. Ironically I think you find what’s popular in Korea right now — it’s stuff like AKMU. “Love Lee” was one of the popular songs right now, which is a very sweet little ditty. We would never hear it here. It just wouldn’t play here at all. But that’s what people are listening to [in Korea]. And the big girl group is IVE, who have no profile at all [in the U.S.].

Whatever.

42:00

Jon: Is NewJeans designed to appeal to forward thinking American music fans? Because it’s working on me.

Kara: Yeah, I like NewJeans.

Jon: I feel like that’s a group moving between Korean and English, but also moving between K-pop maximalism and, if there was truly a forward thinking American pop group right now, that’s what it would sound like, I think, in terms of the reference point one’s borrowing from. Tell me about how IVE and NewJeans — what are they doing differently?

Kara: I think a lot of it comes down to just the performances are very different. The groups themselves are just formed very different. NewJeans are very young, they’re teenagers. And it’s a quality you don’t see a lot in K-pop, at least not really anymore. It’s this ingenue, they’re not quite perfect yet. And their music has that more Western sound to it. The reference point that I hear a lot is PinkPantheress. It does have a more Western appeal to it. Their performance style is…they wear the little high school uniforms. It does have a very nostalgic appeal almost for those of us who grew up during the Britney Spears era…whereas IVE sound more Korean pop. They’re a little more harder edged.

So… it’s OK for one group to embrace a Western sound, but not welcome by another. Got it.

Of course, NewJeans and Ive are both new groups, having debuted in 2022 and 2021, respectively. And if these young women are still recording in 2032, my guess is their sound will have evolved into something much different than it is today. Because that’s what artists do. They grow.

And as an aside, I think that Britney Spears comparison is just … off.

The point of this post isn’t to encourage readers to harangue the podcast host or his guest. In fact, I hope you choose to ignore them and talk amongst yourselves. As someone who has been on the receiving end of severe harassment (both pre-Twitter through present day) for articles and reviews I’ve written — as well as for things I never even said — it’s really unpleasant. But that, I suppose, is the whole point.

I’m too tired to get into why English is pushed so much in Korea — and much of this world — cough colonialism cough. But I wanted to leave you with an academic’s take on this whole thing. In a series of tweets on Twitter, Professor CedarBough Saeji — who teaches Korean and East Asian Studies with a focus on Korean contemporary culture in media — made a succinct point about K-pop, singing in English and being pigeonholed:

“I personally think non-Korean artists who work in Korea and make K-idol pop style are K-pop, so I really don’t see why it can’t be K-pop and in English. But if it’s not, if it loses too many characteristics of K-pop for you (or me) to think it’s K-pop anymore, that does not mean the end of K-idol pop, it just means the growth/evolution of that artist/group. I would hate it if someone said to me ‘you’re a scholar of Korea, you can’t write about China.’ And that’s the closest I can get to seeing it from the artist perspective. They get to grow and change and figure out who they want to be, learn new things. Andre 3000 released a FLUTE album. I don’t see why any Korean artist can’t explore, too.”

If there are any notable errors in this post, please let me know and I will add a correction and tag you in it (unless you would prefer not to be acknowledged). If we just have differences of opinion, I can live with that.

Recommended reading:

• Why Can’t K-pop Groups Speak English Better?

• South Korea’s Criteria for Military Exemption is Outdated

• Suga: Road to D-Day review

© 2023 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

3 thoughts on “NYT’s Podcast Questioned Whether K-pop Should Only Be Sung in Korean”