By Jae-Ha Kim

Substack

December 7, 2023

I want to address a topic that goes beyond the are they or aren’t they K-pop artists if they sing in English dialogue — which was a big portion of that NYT podcast that I wrote about earlier this week. But first, a brief recap of that hot mess:

In that 47-minute long discussion, the host and his guest explored the use of English in K-pop songs. Their general consensus was that if a Korean artist is singing in English, it’s not unique anymore, because they’re doing the same thing that Western artists do:

[Jung-kook’s “Golden” is] an American album with a Korean face on it basically. So I think if I was a listener that was like, “Oh, this is what a K-pop guy can do? It sounds just like Justin Timberlake.” Why do you need a Korean guy doing Justin Timberlake when we have Justin Timberlake?

This could have been an interesting topic if they had addressed their own implicit bias as well as the obvious question: Why is it that when white European performers choose to sing in English — even though their native language isn’t English — no one accuses them of tapping into an already-saturated market of songs performed in English? We know why. Because to a certain sector of our population, white people singing in English is the norm, whereas Asians — even Asian Americans — appear foreign to them. So for these folks, it’s weird hearing ethnically-Asian musicians singing in English.

On a personal level, I experienced this language bias in graduate school, when I was studying journalism. My instructor wanted to know why Asians couldn’t pronounce R’s and L’s. I don’t know why she even asked me, since my English pronunciation is perfect. (Actually, I do know why. We all do, right?) She also wanted to know how long I’d lived in the U.S., because she said I had an unusual writing style.

Reader, that unusual style I exhibited was courtesy of the AP Stylebook, which is the norm in journalism. It’s the same style all of us students used, some better than others. But because of the way I looked (e.g. foreign), she assumed things about my English-language skills based on who she perceived was a foreigner (me) and who wasn’t (my fellow classmates, who were all white or Black). This highly-educated woman had no concept that Asian languages have different alphabets than English.

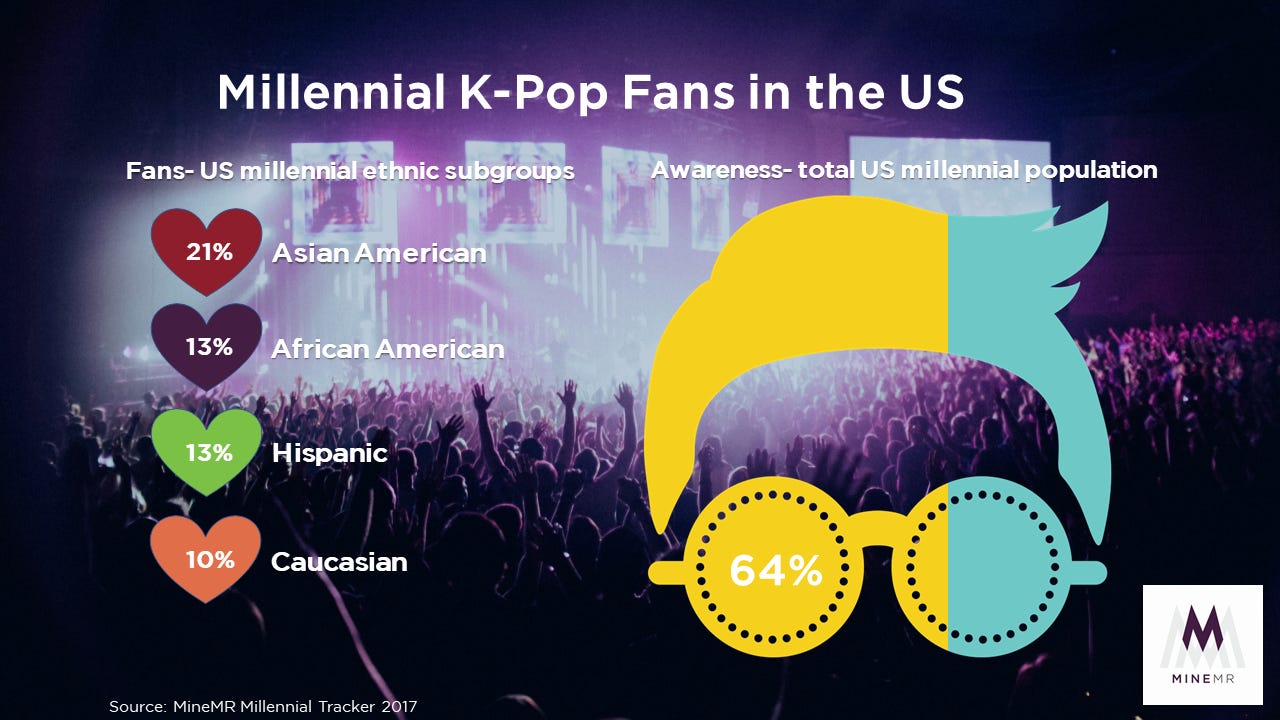

Getting back to the podcast and the perception of who should or shouldn’t sing in English: who do these folks think listen to K-pop in the United States? Are they visualizing a sea of only white faces nodding their heads along to “Seven”? Do they believe that English-language K-pop songs are being made solely for white people’s enjoyment?

White people make up 75.5% of the population, according to the U.S. census. According to a report by Statista, 29.4% of U.S. respondents viewed K-pop as being very popular here, while almost 31% said it was quite popular. They don’t break down which ethnicities are the biggest consumers of K-pop. But a separate study by MineMr showed that 47% of U.S. millennials who consumed K-pop music were minorities.

And yes, I know that statisticians are cringing at how I’m utilizing these figures. Heck, I am, too. But I’m not writing an academic report here, so bear with me.

I rarely hear Asian Americans or Hispanics — the population that some people perceive as not necessarily being English speakers — complaining when a K-pop song is released in English. But there’s so much handwringing from white experts, who want to protect Korean artists from … what exactly? Cultural appropriation? Reverse cultural appropriation? Language preservation? You tell me.

There is a portion of the U.S. population for whom BTS in particular was (and is) a huge connection to their culture: Korean adoptees. From a diaspora point of view, BTS’ music and fame was a welcome catalyst for adoptees to get a glimpse of a heritage that literally was foreign to them.

After BTS began appearing on U.S. television, I received hundreds of emails from adoptees who weren’t K-pop fans, didn’t speak Korean, had never gone back to South Korea … and had been raised to regard themselves essentially as white. But after watching BTS perform on awards shows and late-night chat shows … after seeing them on covers of magazines … some adoptees had an epiphany and wanted to know more about who they themselves were — something that they hadn’t even addressed with their own family members.

Obviously, what I’m talking about isn’t applicable to every single adoptee’s experience. Adoptees aren’t a monolith. But the adoptees who reached out to me shared similar stories — they were adopted by white parents and were often the only Asian child in their school and/or neighborhood. They were bullied for how they looked. Their new families didn’t incorporate Korean culture into their lives. Or, if they did, it was perfunctory (like an annual outing to a local Korean festival). They rarely ate Korean food at home. No one taught them Hangul. Some adoptees explored more of their culture when they went away to college. But others didn’t do so until they discovered BTS.

At this point, let me add that if you are an adoptee and BTS wasn’t the group that spurred you on to explore your Korean culture, I get it. I’m merely relaying what was said to me repeatedly over the past five or six years … and it was always about BTS, who was their gateway to Korean culture.

I’ve interviewed many Korean adoptees for my articles about Korean culture and music. I’ve also received unsolicited emails from adoptees who said they reached out after reading my work or seeing my posts on social media. Many of them told me they felt comfortable writing to me because I’m ethnically Korean, too.

Here are a few excerpts from my BTS cover essay in Burdock magazine, where Korean adoptees shared their experiences:

“I grew up always trying to fit in with my American friends,” said Diana Otwell, who resides in Jacksonville, Florida. “I [had] never really embraced my Korean heritage. I never had any Korean friends. I was always embarrassed and tried to run away from who I am. I found BTS a few months ago after watching them on ‘Carpool Karaoke’ (a recurring segment on ‘The Late Late Show with James Corden’) and just got sucked in. It took seven humble, courageous and resilient young men to teach me that I should be proud to be Korean. As a result, I’ve started to learn Korean and want to take my family to Korea.”

“One of my favorite things is to watch awards shows where BTS perform,” said Rachel Lesiw, who was happy her children were growing up with the representation she never had as an adoptee. “It’s not just their performances that I like. It’s hearing the crowds go absolutely insane cheering for them. After BTS appeared for the first time on ‘The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon,’ Questlove was in awe of them and their fans. He didn’t think that kind of following existed anymore, but it turns out it does. And BTS has them.”

“I turned around and yelled, ‘I’m not Chinese or Japanese. I’m Korean!’” adoptee Melissa Lindemann recalled yelling at her school bullies. “Of course, I really had no idea what being Korean even meant. But when I saw BTS perform on the ‘American Music Awards,’ it finally hit me and I teared up. I realized that I had been ignoring this part of me for too long. I felt guilty, sad, moved and happy. How ironic was it to finally see my roots so widely embraced by American culture, before I had embraced it myself?”

I’m not including the emails and messages from adoptees who talked specifically about the impact of BTS’ English-language songs, because many of them were so painfully personal that I didn’t want to even ask if I could share those private stories.

So my point — and I do have one, I promise! — is that if you say that a Korean man like Jung-kook shouldn’t be singing in English, because that takes away from his Korean K-poppiness, what are you saying about Korean diaspora? (And to be clear, I am an immigrant but I am not an adoptee.) We speak English. Some of us are bilingual, but others don’t speak any Korean at all. But for those who can only speak English, does that take away from their Korean heritage?

I know some of you will say, “But, Jae, a K-pop star singing in English and a Korean adoptee speaking only in English in an English-speaking country are two different things.” And you’re correct. However, my contention is that there’s a biased perception that ties all of this together.

So when naysayers say that Jung-kook’s English-language songs were an attempt to woo more American fans, I say: so what? It’s a smart business move that also challenged his creative artistry. (You go try to sing a song in a language that shares nothing with your own and see how difficult it can be.) And aren’t Korean diaspora — U.S. nationals, no less, who only speak English — part of that American fandom that is being wooed?

Prior to that podcast, I had interviewed four-time Latin Grammy Award winner Andrés Cepeda about what it means to be bilingual. The Colombian musician told me:

Being bilingual has helped me a lot to communicate [in] my music – not only in English-speaking countries, but also in European countries and other places. And it’s been fun, because my first experiences singing were in English, since I was in the school choir [where we performed the songs] in English.

I’m well aware that I’m all over the place in this newsletter and that some of what I wrote may be a stretch. But it’s a feeling that has been resonating within me since all the hullabaloo (pre “Golden” years) over some Korean artists releasing all-English songs and albums.

tl;dr It’s really gross to tell people that their identity is determined by what language they choose to speak or sing in.

P.S. Apparently I am incapable of writing anything under 1,700 words these days. Mea culpa! (And look at me: I’m speaking Latin now! Does that mean I’m not Korean or American anymore?)

© 2023 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

One thought on “Part 2: That Podcast & BTS’ Relevance to Korean Diaspora”