By Jae-Ha Kim

Salon (.pdf)

March 8, 2024

The following contains spoilers for “Past Lives.”

“Past Lives” was released in June of last year, winning a slew of awards leading up to the Oscars. And while some praised what they perceived as a bittersweet love story, the film’s strength is in how it layers in a complex loss that is far more central to Nora’s identity. As someone who, like Nora, navigated two cultures for most of my life, I appreciate the nuanced references in Song’s work that may elude moviegoers unaccustomed to Korean culture. It’s these finely tuned touches that elevate this uniquely poignant film.

Inyeon is mentioned throughout “Past Lives,” but another valid descriptor that runs throughout the film’s core is “melancholy.” It’s a word that co-star Teo Yoo understands all too well. Born in Germany, he moved to New York and then London for university, before relocating to Seoul to pursue the kind of acting career that was elusive to Asian actors in western countries. His diasporic background fueled his real-life melancholy – and it’s a core memory he said he tapped into while portraying Hae-sung.

“I wouldn’t say that I’m a sad person, but I always felt a little bit of somewhat an outsider,” he told Salon in an interview last year. “And there was always an undercurrent of melancholy in my life. And it’s really hard to explain because I don’t know how to define melancholy, but it’s an emotion that you all understand when we feel it or when we see it in music or movies or art.”

This melancholy starts early in “Past Lives.” Not long after their first and only date, arranged by their moms, Nora and her family emigrate from South Korea to Canada. The tweens say a perfunctory goodbye to each other, but both are too young and stubborn to give each other any sense of closure. They don’t promise to write each other long letters. She doesn’t make any cursory attempts to pretend she will ever come back. When he offers a cold, “Have a nice life,” she is fine with that.

Unlike some films centering Korean immigrants – not that there are that many – there are no shots of Nora’s family seeking to immerse themselves into a Korean church to find community. Nor are there any subplots revolving around how difficult it may have been for Nora to blend in as a visible minority. Instead, the film fast-forwards to show Nora as an adult Korean American.

When Nora and Hae-sung first reunite virtually via Skype, they are 24. He has just finished his mandatory military duty required of all able-bodied South Korean men, and she is now living in New York City. Their initial interactions are awkward, as would be expected of anyone who hasn’t seen their friend in a dozen years. But the chemistry is there as they fill each other in on their lives. But over time, due to their 13- or 14-hour time difference (South Korea doesn’t follow daylight savings) and his reticence to accept her hint to come visit her in New York – he wants to go to China to hone his language skills first – she asks for a break.

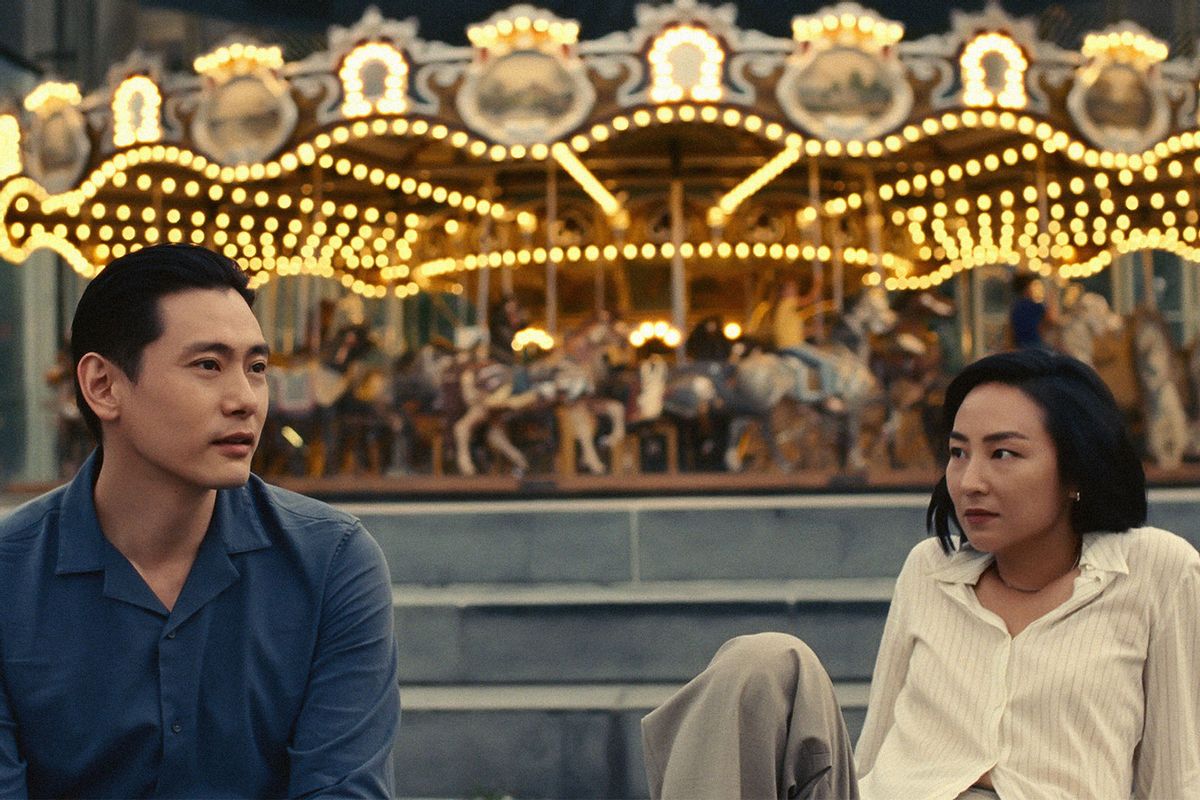

That break lasts another dozen years, when Hae-sung – fresh from splitting with his girlfriend – finally comes to New York. Now in their mid-30s, Nora sits between him and Arthur, who politely listens as Nora and Hae-sung speak in a language he doesn’t understand. Making small talk in English, Hae-sung is profoundly aware of how nice Arthur is, a trait that makes him sad. But Arthur isn’t what stands (or stood) between the two; it’s their history and inability to acknowledge that they meant more to each other as children than they let on.

But now they’re together – for a couple days of sightseeing anyhow. And showing the patience of a man who truly loves and trusts his wife, but who’s also jealous of the past life she shares with this Korean man, Arthur stays home playing video games by himself as Nora shows Hae-sung around New York.

On a ferry ride circling the Statue of Liberty, there is a tender but funny moment that highlights what it means to be a Korean woman. Though Nora has now lived two-thirds of her life outside of Korea, she can’t shake her upbringing. As he prepares to take a selfie of them as a memento, she asks, “Why are you taking this so close?!” He laughs and apologizes right away, understanding her concern. He moves up, asks her to take a step back and retakes the photo. Every Korean woman has been conditioned since childhood that it’s not attractive to have our faces appear too large in pictures. It’s such a weird construct by western standards, but it’s also a fact that Koreans in general are obsessed with small faces. (A common compliment on variety shows is for hosts to comment on how a guest’s face has gotten smaller.) And Koreans know that it’s the man’s job to position himself in a way that the woman will appear more attractive.

This small, but masculine gesture is never explained. But it is Song’s way of articulating that while Nora might speak Korean with a child’s inflection and walk in a bold manner that would instantly identify her in Korea as a gyopo – or an ethnic Korean living overseas – she is still Korean.

That heart-wrenching ending that I alluded to earlier takes place as Nora waits with Hae-sung for his Uber to take him to the airport. After saying goodbye and watching his car drive away, Nora breaks down sobbing. Some viewers have interpreted this as Nora regretting the choices she made. But from a diasporic point of view, it’s more likely that Nora is inherently upset about a life she can barely remember due to choices her parents made on her behalf.

At one point earlier in the film, Nora asks Hae-sung why he looked her up in their 20s.

“Do you really want to know?” he says. “I just wanted to see you one more time because you left so suddenly,” he said. “I was pissed off.”

Maybe that is the reason. Or maybe it is the concept of jeong, a word that’s never uttered in the film, that draws Nora and Hae-sung together after all those years. Jeong refers to an emotional connection between Koreans due to proximity (family, friends, neighbors) or lack thereof (two Koreans running into each other in a foreign country). The jeong that Nora and Hae-sung share align with their inyeon.

For Nora, proximity to Hae-sung reminds her of her younger days living in Korea. But it also reminds her of the 12-year-old girl she left behind to become who she is today. In order to become Nora Moon, she had to leave behind Moon Na-young. While she gained a new identity – one that she’s happy with and accustomed to – the loss of her younger self is profound.

“Past Lives” is available to stream for free on Kanopy, for digital rental or with a Paramount+ with Showtime subscription.

Release date: After its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival on January 21, 2023, “Past Lives” had a limited U.S. theatrical release on June 2, before expanding to a wider release on June 23, 2023.

Running time: 106 minutes.

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

4 thoughts on “American melancholy: The real loss in “Past Lives” isn’t love”