By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

February 18, 1996

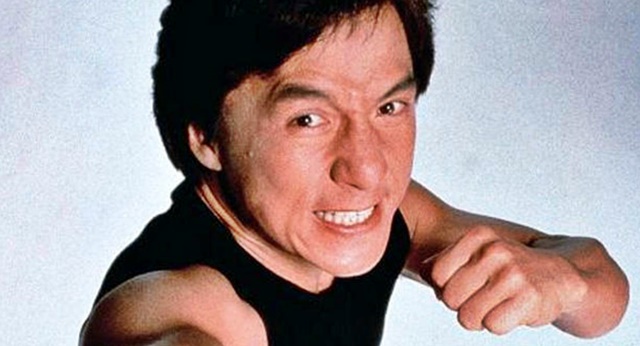

Jackie Chan’s stunt man has the easiest job in film. All of Chan’s action films are full of dangerous free falls, explosions and rapid-fire kung fu fighting, but the stunt man doesn’t have to participate in any of them. Chan insists on doing all the stunts himself and uses his stunt man more as a double.

“I believe all the people who come to my movies buy tickets not to see the double,” said Chan. “They want to see me do everything, which is why I do all my own stunts. My double does things like run from a car into a store.”

Chan, on the other hand, does things like jumping from the rooftop of a 10-story building onto the fire escape of another – without the use of a safety net. Stunts like this make him uninsurable in his native Hong Kong, and also the most adored actor in Asia. He’s hoping that his latest film, “Rumble in the Bronx” (opening Friday at local theaters), will make him a box office star in the United States, too.

The building-jumping sequence is a highlight in the action-packed “Rumble,” his first movie to get mainstream distribution in the United States. Though he ended up with a broken leg, Chan’s primary concern was that the cameramen (he always uses six cameras to film his stunts) captured the action on film.

“We are very careful, but there are accidents,” he said, pointing to scars on his head, arms and legs. “But after you do the stunt and the director yells `Cut,’ you feel great. At that moment, you are the hero.”

Already, the 41-year-old actor has some high-powered fans. Director James Cameron, Sylvester Stallone and Jean-Claude Van Damme admire his work and Quentin Tarantino gushes about him the way teenage girls do about Jonathan Taylor Thomas. At MTV’s annual Movie Awards last year, Tarantino presented Chan with the Lifetime Achievement Award, an ironic honor because Chan is relatively unknown in the United States.

“I had never met Quentin before the MTV Awards,” Chan said, still speaking with a trace of an accent. “He was very nice. I had not known that he admired my work so much. I don’t know why, but suddenly in Hollywood everybody is talking about me. I did an interview at the Sundance Film Festival, and this reporter told me that Jim Cameron had told her that I was his hero. I said, `What?’ It’s probably a good time that I came back to America.”

Sitting in his suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Chan is animated for this interview. Gesturing with his hands and making funny facial expressions to punctuate his thoughts, he speaks quickly, occasionally lapsing into Chinese when his English fails him.

He is a unique combo of actor, martial arts expert and action star. That shouldn’t be surprising considering his influences: Buster Keaton, Fred Astaire and Bruce Lee.

When Chan began making films, producers tried to mold him into the next Lee. Those projects failed miserably. So Chan forged his own identity by incorporating humor into kung fu films. While he’s respectful of Lee, whose “Enter the Dragon” was a breakthrough martial arts film, Chan pointed out that his films include things that Lee was unable to execute.

“He didn’t do his own somersaults,” Chan said. “I am the lucky one because I was trained for a lot of different things.”

Lucky isn’t the appropriate word to describe his early years. Although Chan is a multimillionaire today, he was indentured at age 7 to the rigorous Chinese Opera Research Institute by his impoverished parents. For the next 10 years, he trained up to 19 hours a day to perfect his martial arts, acrobatics, dancing, singing and fencing skills. He was preparing for a career with the Peking Opera, but after his training, he turned instead to films, finding work as a stunt man. In 1975, the Hong Kong film industry dubbed him Lee’s heir apparent, something the public wasn’t ready to accept. By 1978, he had reinvented himself as a comic action star. This time he succeeded.

Since then, Chan has made more than 40 films, most of which had three common elements: Chan plays martial arts experts who aren’t exempt from pain; his rhythmic fight scenes are as meticulously choreographed as pas de deux; and while he often gets the girl, he doesn’t bed them.

“In Asia, we don’t do that,” he said, referring to sex scenes. “I keep my own rules, and all these years, I have success with my own rules. But things are changing a little bit now, even in my movies.”

For instance, he and a co-star share a chaste kiss in “Rumble in the Bronx.”

“I believe that (my female fans) are growing up now, and they accept that I can have a girlfriend in a movie,” Chan said. “I should be a real human being. I can’t always say no to a small kiss in a movie. But no sex, no love scene, no dirty jokes. . . . I cannot stand sex and kissing in movies. It’s an Asian thing.”

Chan found out early in his career that his fans – especially the women – didn’t care to know that he was “a real human being.” After it was reported in 1985 that he was in a relationship, a Japanese girl committed suicide by jumping in front of a train. Another showed up at his office and drank poison. Since then, he has kept his relationships private. But this year, he’s been opening up a bit.

“I have a secret for you,” Chan said. “If you ask me, `Are you married? Do you have children?’ I’d say, `No.’ But I’d be lying. I’m a normal person. I have a (wife) and now we have a (13-year-old child), and I’m finally beginning to tell my fans this, because many of them are big now, and some of them are married already and have their own babies.”

Chan’s parents are proud of his achievements, but his mother still won’t watch his films, he said. She doesn’t approve of show business and is much more impressed by the honorary doctorate in social sciences that Hong Kong University recently awarded him.

“She likes `Dr. Chan,’ ” he said, laughing. “I think if she saw my films she would see that they aren’t like what she thinks they are. I’m more like Donald Duck than a mean fighter. It is funny because personally, I am happy-go-lucky and I hate violence. But if I hate violence, then I can’t make action films. This was my dilemma. So I set up the rule for myself – lots of action, no violence, comedy, but not dirty comedy. When I’m fighting, it’s like dancing.”

Chan also has this rule that he won’t do anything he can’t do well. While he’s fascinated by computer technology and special effects, he doesn’t have a grasp of how it all works . . . yet.

“I want to be like Steven Spielberg and know how to do everything,” he said. “But I don’t know how. And I would rather not do it until I know how. I know action. So I will concentrate on action for now. Before I can do computers, I have to learn English better. I can speak it OK, but I cannot read English. . . . So for now, I do my basic thing, which is the action movie. There, I am the teacher and I can teach many people how to find the right camera angles. With special effects, I’m like a kindergarten kid.”

It’s good that Chan is planning for his future. Though he’s still in great shape, his body has been battered in the filmmaking process, and he estimates that he’s got another four years of acting left. Special effects would mean no more broken limbs or nose fractures, and no more brain surgery (he cracked his skull a decade ago).

“Why do I keep doing this?” he rhetorically asked. “Many people ask me this. I ask myself this. I think I just want to be remembered the way people remember Buster Keaton, John Wayne, James Dean, Bruce Lee. . . . They’re remembered.”