By Jae-Ha Kim

By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

December 1, 1991

It has been a long time since David Bowie has felt this good about himself. The former David Robert Jones, Ziggy Stardust and Thin White Duke has carved out a new musical niche without creating a new persona to play it out.

Bowie is in Liverpool, England, on this day, congenially promoting his group, Tin Machine. He’s newly engaged to the model Iman, and sips on a cup of hot tea, his substance of choice these days. Mentally scanning his flamboyant 25-year career, he comes to the conclusion that his life, as that of most musicians, would make a boring film.

“There’s really not much there to explore (about musicians),” he says, his laughter crackling over the phone lines. “We really are the Monkees. I’m even Davy Jones, that’s the worst part of it.”

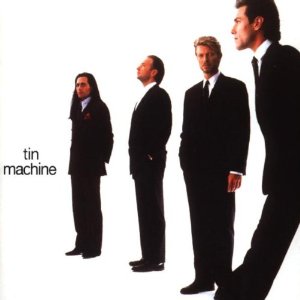

The elusive musician isn’t quite as elusive as he used to be, primarily because he knows that coyness won’t work when it comes to promoting Tin Machine, an unproven live group that touts one superstar and three relative unknowns. The four-man Machine runs on equality, Bowie says, even though many people still preface the group’s name with his.

Despite being able to boast the Bowie name, Tin Machine has received its most press to date for putting traditional nude kouroi statues on its cover. When American retailers balked at the depiction, Tin Machine’s record company castrated the naughty bits for the U.S. market, creating a cover that is fundamentally more disturbing to look at than a naked male statue.

“We thought the whole thing was ridiculous and childish,” Bowie says of the controversy. “I suppose I should be grateful that at least they didn’t put little surf shorts on the kouroi.”

It’s safe to say that those who found the naked kouroi obscene won’t approve of guitarist Reeves Gabrels’ affinity for using a vibrator as a pick. “He likes playing to the beat of a different drum,” Bowie says, “so we let him.”

Having just completed a tour of Europe, Tin Machine is winding its way across America. The group, which also includes Soupy Sales’ kids, drummer Hunt and bassist Tony, will perform a sold-out concert Saturday at the Riviera.

Tin Machine’s live shows are surprisingly raucous. Heavy metal style grunge guitar backs Bowie’s typically smooth vocals, which reverberate with edgy invigoration on such songs as “Baby Universal.” With a total of 74 years of experience between them, the musicians create Gentlemen Rock, a genre of music Bowie might have bristled at during his androgynous days in the ’70s. But at 44, Bowie views this title as a badge of honor for not only having survived rock ‘n’ roll, but having thrived in it.

“One of the reasons that drew us together is we’re all of a certain age, me being at the top of the cake,” he says. “We’ve all lived out some pretty hairy lives. For myself personally, even though I have made records that weren’t considered commercial successes, I don’t feel the need to try to block them from my past. I’ve been pretty fortunate in that I’ve been able to work with people who I admire and worked well with.”

The scraps of Tin Machine began to mold in late 1987, after Bowie had completed his gargantuan, artistically barren Glass Spider Tour. Through his press liaison, Sara Gabrels, Bowie got a tape that he thought was everything that the tour, in support of the LP “Never Let Me Down,” wasn’t: fresh, basic and avant-garde. The musician was Gabrels’ husband, Reeves. Bowie added the Sales brothers, whom he had known from the ’70s when they backed Iggy Pop, and Tin Machine took shape.

“We didn’t get into this project expecting the public’s perception of us to be as total equals,” says Hunt Sales. “We’re not stupid. In fact, I don’t think there’s one of us who didn’t think in the beginning that we were playing on David’s record, rather than our record.

“But David made it known that it was a collaborative effort. I think what’s more important than any public perception is that within the band, we don’t feel like it’s David and then us. We are totally equal. And our audience is very respectful of that. We don’t get kids coming to our shows screaming out requests for `Golden Years’ or `Young Americans,’ which is a good deal because it just ain’t going to happen.”

According to Bowie, that won’t ever happen at any of his concerts. When he promoted his highly successful Sound and Vision Tour last year, he threatened – or promised, depending on how you look at it – that those concerts would be his swan song to the oldies. Of course, Bowie announced in 1973 that he never would tour again, too. If longtime fans are disappointed by his vow of greatest hits silence, he’s sorry. But experiencing artistic growth is more important at this phase of his life than racking up the dollars he already has plenty of.

“My priority is to accomplish things that I think are artistically important, at least to me,” Bowie says. “I always feel grateful that I have some audience that will come along with me, because I certainly don’t have the pulse on what is happening musically. But I’m elitist enough to think that I would probably do whatever is going to be happening first. That may not be in vogue with the (public), but I have to do it. There’s no point in just getting out the wheelchair and gliding out to what everybody knows. It’s been done. God knows I’ve done it.”

After taking Tin Machine through 1992, Bowie will work on a solo album, make his film direction debut and continue his acting career. He recently finished filming David Lynch’s upcoming feature film, “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me,” continuing the “Twin Peaks” TV show saga. He plays a “remotely alien FBI agent.” Cast members include singer Chris Isaak. Asked what it was like having two pop stars in the movie, Bowie joked: “Well (Chris) is the pop star. I’m a rock god!”

“Rock god. Don’t you love it?” Bowie asks, laughing. “I just think the phrase is so funny and gross. I like it. There was a line in the `Doors’ movie that I thought was chauvinistic, but very funny. A girl says to Jim Morrison, `- – – – me, rock god!’ but they didn’t have the nerve to leave the line in the movie. Those four words summarize the entire history of rock ‘n’ roll. Try making a movie about that.”