By Jae-Ha Kim

Chicago Sun-Times

May 7, 1995

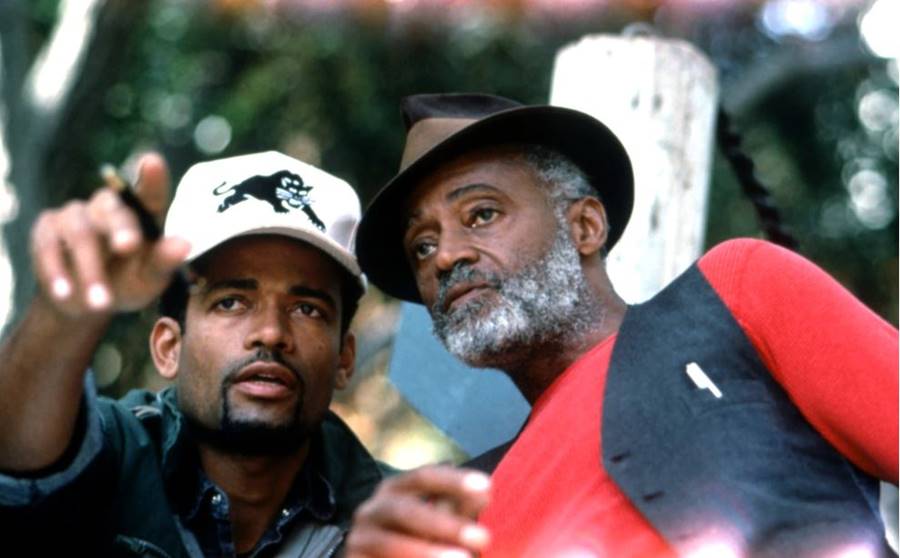

Dressed in baggy black pants, an oversized shirt and a black cap touting the name of his latest film, “Panther,” Mario Van Peebles sits barefoot in his suite at a downtown Chicago hotel. A neat goatee does little to disguise the chiseled face that became his calling card in films such as “Posse” and “New Jack City.” For “Panther,” he spends most of him time behind the camera; Peebles directed and co-produced the film with his father, Melvin Van Peebles.

Based on the elder Van Peebles’ book about The Black Panther Party, the father-son team has made a controversial film that has been slammed by members of the former Panther Party as well as conservatives who say the film is a romanticized version of a violent organization. Peebles said there’s no debating that the film is fiction, but that it’s true to the spirit of the Black Panthers.

Q. What do you say to detractors who say you are presenting fiction as fact?

Peebles: “I say that we have made a film that is a work of fiction, but that the film drew on information from documented historical facts. I’m not going to say that everything that happened in the movie happened in real life in the 1960s. But our point wasn’t to make a documentary or a piece of work that would be implemented into students’ studies. It was to make an interesting film that would make people think and question what really did happen.”

Q. Why is it so important that this story be told?

Peebles: “There’s this quote that one of the things education is used for is to socialize the oppressed to the oppressor’s point of view. One of the things we dealt with in this film is that most people had only heard what the media said about the Panthers – that they were scary, militant guys with guns who were very angry at everything and everyone. Very few people knew that the Panthers had breakfast programs for children or that they helped implement sickle cell anemia programs for the poor. In school, you learn about slavery, but you don’t learn about empowerment.”

Q. How do you respond to the criticism that all the bad characters in the film are white and that all the good guys are black?

Peebles: “That’s just not true, and yet that’s what some critics have said, even though one of the strongest villains is a black drug dealer. If you had made `Forrest Gump’ with an all-Asian cast or an all-black cast and had the only white character walking around in a daze going `Gump shrimp,’ people would’ve had a fit. The thing is, (minorities) are so used to being mistreated on screen that we’re just happy to see ourselves up there. We’re like, `Oh fine. Whatever.’ But you look at the old Westerns and the black guy was the scared butler, the Asian guy was the houseboy, the Mexican guy had a big sombrero and the Indian was dead. And no one said a thing.”

Q. As a director, how careful are you not to present stereotypes of other races?

Peebles: “Very. When I (directed and starred in) `New Jack City,’ that was the first time I was in the power seat. I decided to make one of the central characters Asian because I knew that if it was hard for me to get roles, it was probably harder for an Asian brother to get recognition. The casting agency sent me every little, round, short (Asian) guy with glasses doing the comical, subservient thing, and we all laughed. And then I realized that was the equivalent of what had been done to (blacks). So when Russell (Wong) came in at 6-foot-1, great-looking and not a buffoon, I said, `You’ve got the job.’ And originally, the white cop role was written as a total idiot, and I said, `You know what? I don’t want to do that,’ because then I would’ve been guilty of doing what other people did to blacks. So I called up Judd Nelson and made him this hip, cool cop. If anything, my character was more strait-laced and uptight than anyone else.”

Q. You made “Panther” on a $9 million budget, which is tiny by Hollywood standards. How difficult was it for you to get this film made?

Peebles: “It was hard. It took us five years. We shopped the idea around, and one fellow told us that he liked the idea but that Hollywood wouldn’t care unless we told it from a mainstream perspective. And then he rattled off all these movies told through the white man’s point of view, like the Native-American experience told from Kevin Costner’s perspective (in `Dances With Wolves’). Or the black experience in `Mississippi Burning,’ with Willem Dafoe and Gene Hackman as the stars. And the story of Japanese internment camps told not through the Japanese, but via Dennis Quaid who was married to a Japanese woman. Or when a film’s made about martial arts, you just know that the karate kid isn’t going to be Asian, but Ralph Macchio. He went on and on and it was like, `Wow!’ ”

Q. Did you think about what he said, knowing that you could make a bigger budget film if you had a mainstream star?

Peebles: “Yes, and we could’ve done that because the Panthers had a lot of white support from high-profile people like Marlon Brando and Tom Hayden. A lot of people wanted us to tell the story from say, Tom Cruise’s point of view. If we were negotiating now, I’m sure they would say, `Make one of the lead Panthers white, and get Brad Pitt to star in the film.’ But I thought about what my dad said, which is that history goes back to the winner, and you’re surely not winning if you’re not telling your own history. So we held off until we could make the film our way.”

Q. What was your wake-up call to discrimination?

Peebles: “After I graduated (from Columbia University with a degree in economics), I got a job as a budget analyst. I wanted to get into films, so I quit my job and modeled. I was at this Calvin Klein go-see where all these beautiful models were in the waiting room – Iman, (Dutch-Japanese model) Arianne, my sister. . . And (the bookers) saw everyone but me. I was like, `Ah, saving the best for last.’ And then, click, the lights went out, literally, and the lady said they would never use a black model. And what she really meant was they’d never use a black male model. Until then, I had never really seen color.”